Early modern English and German collecting networks and practice: Medicine and natural philosophy

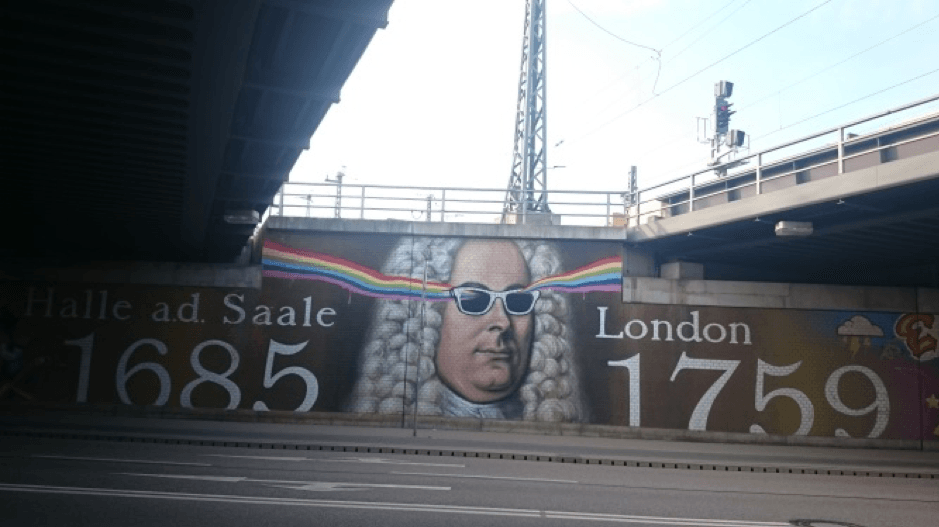

On the 8-9 June, 2018, I had the privilege of attending “Early modern English and German collecting networks and practice: Medicine and natural philosophy,” the first of three workshops in the Collective Wisdom: Collecting in the Early Modern Academy project headed up by Anna Marie Roos and Vera Keller. The workshop was hosted by the Leopoldina Centre for Science Studies in Halle, appropriately coinciding with the Handel Festival. As a historian more familiar with early modern England than early modern Germany, this was a valuable opportunity to learn more about German sources and scholarship in conversation with English counterparts.

The workshop was an invitation to probe the role of academies (specifically the Leopoldina and the Royal Society of London) in the shift from wonder cabinet to the Enlightenment museum, exploring how collecting networks and practices changed between roughly the mid-seventeenth and mid-eighteenth centuries. While some papers addressed these academies directly, the workshop as a whole went further to consider them as part of a greater diversity of contexts and networks in which collecting practices were pursued for their epistemological value.

“Collective wisdom” neatly sums up the play between early modern collections (materiality, circulation, preservation and order) and the collectives behind them (academies, societies, different kinds of networks such as correspondence and trade) that emerged during the workshop. In these collection networks and practices, what travelled and what did not? What was transmitted over time and space, and what remained relevant only to the specific social context that brought them together? This “collective wisdom” could be read as knowledge gained from studying collections (classification, experimentation, observation), knowledge as a collective pursuit (networks, societies, educational institutions, guilds) and the collections generated through object-based study and exchange (archives, correspondence, journals). Most of the sources discussed were of necessity this last kind, the paper trail, reflecting early modern anxieties about the preservation of collections in the early days of collection institutions.

The two guided tours during the workshop provided a very tangible reminder of the role of institutionalisation for the survival of collections. The archives of the Leopoldina gave a glimpse of a rich resource of early publications and the academy’s active collecting role, but was also a reminder of the absence of the Leopoldina’s lost collections. In contrast, the visit to the Francke Foundations was a multisensory encounter with an extraordinarily well-preserved Kunst- und Naturalienkammer, still housed at the top of the original building, whose stairs we sweated our way up in the heat of the summer afternoon. We were awed, intrigued, curious and delighted at the long room with its models down the centre and purpose-made cabinets along the walls (kunst at one end and naturalia at the other) and very reluctant to leave. Yet while the rare state of preservation gave a sense of direct access, it introduced other questions of interpretation, given the distance between the institution as an early modern utopian vision of protestant piety and a twenty-first century museum. The Leopoldina and the Francke Foundations represent two very different uses of collections for the generation and transmission of knowledge: the first tended more towards scholarly and medical networks, an impression enforced through the survival of published and manuscript collections, while the second was part of a larger social project in which the displayed objects and models provided a view of the world in microcosm in a pedagogy that was intended to inspire the viewer to the mission field. Many of the objects were themselves sourced through early mission networks, particularly to southern India.

Many of the discussions prompted by these two collections were raised in the workshop papers, including the role of models and play, the arrangement of collections and catalogues, institutionalisation and the preservation of collections, collecting networks and infrastructures, and the implications of urban/rural collecting. Examples of the use of models as pedagogical tools were particularly interesting as they reflect such different approaches to collections as objects of knowledge production and transfer. Kelly Whitmer’s plenary paper “Engaging with Realia in the ‘School of Play’: Useful Knowledge and the Turn to Pedagogical Realism in Early Modern Central Europe” emphasised the role of playfulness, in this case in the pedagogical value of children learning through playing with objects and toys, but also how much adults had to learn from observing them. Anna Maerker presented a very different example of the pedagogical use of objects, the collection of anatomical waxes in the Josephinum, Vienna. Maerker accounted for the discrepancy between the success of the original collection displayed in the natural history museum in Florence, and their widely controversial pedagogical display for the training of surgeons, effectively replacing the role of dissection. In this case, institutionalisation and patronage did not ensure the success of the collection, and the familiarity with wax models as objects of spectacle or amusement contributed to the public ridicule.

Questions of access, publication and secrecy were central in Georgiana Hedesan’ analysis of two catalogues (the Worm and Tradescant museums). Worm’s published catalogue and museum were public displays of his alchemical knowledge, skill and extensive collections, yet crucially did not disclose alchemical secrets. Classification, ordering collections and the role of publication were brought up in several of the papers, as in Vera Keller’s study of “hyphenated objects” and Thomas Ruhland’s reconstruction of the organisation of the Franke Foundation’s Kunst- und Naturalienkammer according to Linnaean classification, based on a detailed study of the catalogue against the objects and their labels. In contrast to the relative stasis of this collection, living collections such as gardens were important sites of experimentation and ordering precisely because of their inherent mutability (a trait plants and people share), as I discussed with the example of the Oxford Physick Garden.

Julia Schmidt-Funke’s plenary “Studying Nature in the City circa 1700: Danzig and Frankfurt” demonstrated how importance of urban collecting and collectives using the example of two multidenominational cities without a university. This “urban history of science” emerged within the city’s social fabric and infrastructures: the merchant trade, the postal service and the importance of collecting and experimentation organised at the domestic level. A fascinating glimpse into rural private collecting, Anna Marie Roos’ paper on James Petiver’s recently rediscovered travel diary emphasised the importance of “scientific peregrination,” which in Petiver’s case was a means to establishing his network and credentials in the absence of a university education. Such networks, upheld through correspondence and travel, are also reflected in the album amicorum or friendship albums discussed by Maria Avxentevskaya. This prompted a discussion about why this particular collecting culture was found in the German but rarely in the English context – one of the few examples during the workshop of clear differences along these lines. Bringing together scholars working on German and English sources allowed a range of factors to be brought into conversation – including religion, class, the urban/rural, the domestic/institutional, display and use – without collapsing into binary comparisons.